13 Tips for Writing Effective Quality System Investigative Reports

- Posted by ISPE Boston

- On September 24, 2020

By: Howard Sneider

Completing an investigation is one of the most strenuous responsibilities of individuals that work in quality system compliance. The investigation usually includes an investigative report to document the events and analysis of the proceedings. The investigative report is, with few exceptions, an irrevocable account of what has occurred and will largely determine the trajectory of actions coming out of the investigation. Because the report is such a critical document it is crucial that both content and presentation of material are thoughtfully prepared.

The investigative report will focus on elements pertinent to the investigation and will aid in identifying actions that shall be implemented to prevent future noncompliance. The larger the target that is identified by the investigation, oftentimes the more disruptive the required changes will be to eradicate the cause of non-compliance. A valid, reliable, accurate, and comprehensive report will enable a swift and effective remediation, and will permit a return to normal activities as quickly as possible.

The investigative report will also serve as a record to the investigative process. It is important that the investigative process is thorough and well documented. Although the investigation may be conducted while the pertinent facts of the noncompliance are well known and easy to appreciate, the report may be reviewed several years later, possibly without the benefit of the author’s availability to clarify any inconsistencies or ambiguities. The report must be clear, polished, and present all pertinent information on which the investigation’s conclusions are based upon. It must be written in a way that any person can understand it without having to reference other materials.

Because the investigative report may be used to support legal claims it is important for it to be thorough. An investigative report with an appropriate level of content will be able to provide decision-makers with enough information to determine if further action is warranted. However, too much information can also be detrimental because it can distract from the focus of the investigation. Additional information can introduce the notion that the facts are being presented in a way to highlight a finding that is not related to the main topic of the investigation. Extraneous information can be interpreted as an investigator’s bias and can call into question the validity of the report. The content of the report must be verified by reviewers and those approving the report and any additional information may unnecessarily prolong this step. Non-essential information may be protected in nature and having the information uncovered in the investigation may hamper otherwise desirable actions coming out of the investigation. The additional information included in the report may also reveal non-compliance outside the scope of the investigation that may be detrimental to the entity being investigated and investigator.

In consideration of the importance and critical requirements of the investigation report, I have provided some guidance below on how to approach and compose an investigation report.

- Begin with the end in mind – This bit of wisdom, best known as Habit 2 of the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, should be applied specifically to the outcome of an investigative report. Begin by reading a great report in your organization. Perhaps review a report that uncovered a problem that was particularly difficult to assess. Talk to the author(s) if at all possible to understand what challenges they met while conducting the investigation. If the author(s) are not available then find another person who is familiar with investigations. Developing this type of advisory relationship will improve the chances that your investigation will be thorough and conclusive.

- Start Right away – There are several benefits to starting a report as soon as possible. The longer a report is delayed the less interest there will be in pursuing corrective actions. Other, more pressing problems may preempt follow through on the investigation if the report is delayed. Ideally, the report is started as soon as the investigation starts so that a time table can be captured and also so that investigative notes can be recorded. The process of writing the investigation report may provide new insight into the cause of the issue.

- Treat it like a project – It is important to keep the momentum and the urgency to complete each investigation. Ensure that each step of the investigation is scheduled and that the progress of each deliverable is tracked. This practice will help ensure that there is a sense of urgency to complete the investigation, that there is a momentum towards reaching a conclusion, and it will help prevent procrastinating on the delivery of the report.

- Visit the scene – If possible, visit the location of the incident. If possible, visit at the same time the incident occurred. If possible, visit the scene under the same conditions that the incident occurred. Recreating the scene helps to elucidate the conditions under which the incident occurred and may help to identify the what, who, where, when, how and why of what occurred. Talk to the people involved and, if possible, get accounts of the events from more than one eyewitness. However, be weary of hearsay from individuals.

- Ask the what, who, where, when, how and why of the incident – the investigation report, at a bare minimum should include a description of these pertinent facts: a full description of the tasks being carried out, materials and equipment used, relevant procedures, environmental factors, etc.

- Keep asking why – Ask “why” five times to try to find the source of a problem. The 5 Whys technique is really only a tool to help investigators ask questions. There are no rules as to what questions should be asked or how deeply the line of inquiry should proceed. The success of a 5 why inquiry depends largely upon the knowledge and persistence of the investigators. Asking others for their contribution will broaden the diversity of thoughts and opinions that the 5 whys are based on and will improve the outcome of the exercise.

- Gather evidence – Any evidence related to an event or observation, such as personal accounts, the locations of parts or positions of equipment, parts or components, or relevant documentation must be preserved, secured, and collected through notes, photographs, and witness statements. If possible take possession of documents and equipment, as appropriate to ensure a thorough investigation.

- Stay on Track – The investigative process is likely to uncover issues that are unrelated to the scope of the investigation at hand, but may also require investigation on their own. It is important to maintain the scope of the current investigation focused on the original issue and to open investigations of unrelated issues separately.

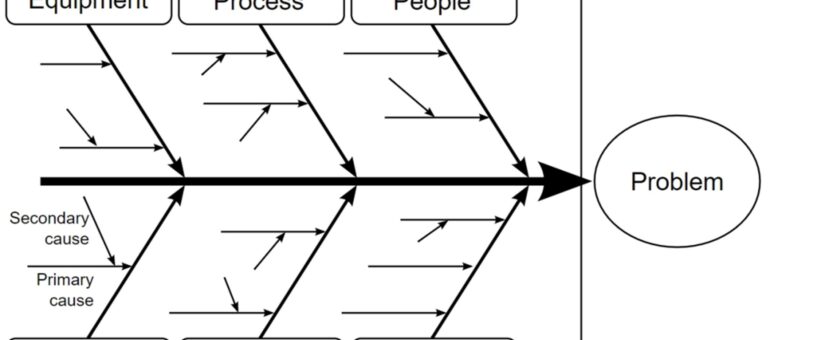

- Create a Fishbone Diagram – after the problem statement of the investigation is identified, enquire how each category that contributes to the problem statement may have caused the problem to occur. The benefit of performing this analysis in a diagrammatic way is that the number of causes for each category may be visually appreciated. The mind likes symmetry and balance and will work extra hard to develop credible causes for areas that are sparse.

By FabianLange at de.wikipedia – Translated from en:File:Ursache_Wirkung_Diagramm_allgemein.svg, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6444290

By FabianLange at de.wikipedia – Translated from en:File:Ursache_Wirkung_Diagramm_allgemein.svg, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6444290

- Include an Executive Summary – A complicated investigative report can be hundreds of pages long. A brief executive summary can help a reader understand much more of the report by providing some guidance as to the general contents and direction of the main body of work. It should provide a summary of the work but not contain any information that is not repeated elsewhere in the document.

- Remember the 5 C’s – Make sure that your report can answer the questions posed by the 5 C’s. The 5 C’s tell the whole story of why the investigation was started, what it discovered, the ramifications if changes are not made and the beneficiaries if actions are taken.

- Criteria (what should be).

- Condition (the current state).

- Cause (the reason for the difference).

- Consequence (effect).

- Corrective action plans/recommendations.

- Avoid including the following in the report:

- Any confidential or proprietary information

- Any subjective opinions

- Any recommendation, unless required by the client

- More than six or seven major findings – More findings may be prioritized as less substantial

- Minor, trivial details unrelated to the central scope of the audit

- Names of individual employees associated with specific findings

- Emotional or argumentative statements

- Acronyms, technical terms or jargon that is not defined in the text or in a glossary section of the report.

- Check your work – it is imperative that the report is run through the included spelling and grammar checker included with most word-processing software. Ensure that you have read through the report several times so that there are no spelling or grammar errors that the system missed (Usually I find that an intended word is replaced by a similarly spelled word).

The above items are in no way exhaustive or guaranteed to be applicable to each investigation. However, I have found that the tools described above are generally helpful when organizing the approach to an investigation. The process of writing an investigative report may be less daunting and more rewarding by keeping the above items in mind. I hope that the reader benefits from these suggestions as much as I have, and I welcome the reader to feel free to contribute their own tools in the comment section below.

0 Comments